Advice From an Ophthalmologist: What You Need to Know About Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration

A wet AMD diagnosis leaves you with lots (and lots) of questions. Forget Dr. Google. We asked an expert to weigh in.

By Susan K. TreimanMedically Reviewed by Laura J Martin, MD

Reviewed: December 2, 2021

What do you need to know — most pressingly — after a diagnosis of wet age-related macular degeneration (wet AMD)? Here, the specialist and researcher Joshua L. Dunaief, MD, PhD, the Adele Niessen Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, addresses the leading worries, fictions, and facts patients bring to his office.

Q: What Is the Single Biggest Misconception Patients Have About Wet AMD?

A: That they will go blind — and that’s just not the case.

People who arrive terrified that they’ll go blind can actually interfere with their own ability to fully understand and comply with their doctor’s instructions. They may have read inaccurate information on the internet — thanks to Dr. Google — that they haven’t been able to put into proper context, or a friend may have told them something that seemed true.

They need to know that total vision loss with wet AMD is extremely rare. Even in the worst cases, where patients lose part of their central vision in both eyes, the peripheral retina usually remains unaffected. These people can be trained to use that part of their retina for some lower acuity vision and, to varying degrees, they can compensate for some of their sight loss.

Working closely with a low-vision specialist or an occupational therapist trained specifically to deal with limited sight, they can master techniques that allow them to perform daily tasks.

Q: What’s Misconception Number 2 on the List?

A: People come in wondering what they did to bring this on. I tell them the passage of time and the genetics lottery are the culprits. That is, AMD is the result of heredity and aging.

Q: What Is Actually Happening in AMD?

A: Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a sometimes-progressive eye condition that causes injury to the macula, the portion of the light-sensing retina responsible for our high-resolution vision in the center of our visual field.

We’re not yet sure why, but we know that AMD is first seen in waste products that collect under the macula, where they appear as little white spots called drusen; that’s the German word for “pebble.” This debris indicates that the patient has the early, dry stage of AMD and could eventually be at risk for some vision loss. But that’s by no means a sure thing.

These particles are made up of immune mediators, lipids, cholesterol, and oxidized proteins believed to be left by damage from free radicals (molecules made unstable by aging, inflammation, or some other process). Our best data suggest that cumulative oxidative damage creates mutations in DNA affecting both the cell nucleus and mitochondria, the energy-producing portion of the cell.

We’re still studying the exact process involved, but we know that the immune system tends to promote more inflammation as we age. That makes people over age 55 most susceptible to AMD. One-quarter of the over-80 population has some form of the condition.

Q: What Are the Signs That Someone Has Developed AMD?

A: Initially, AMD is usually asymptomatic. Most patients first realize they have dry AMD when a doctor observing the back of the dilated eye through a lighted ophthalmoscope (a combined light and magnifying device that illuminates the eye’s interior) sees the drusen collecting under the macula. Right now, only a doctor can detect the presence of this debris. But in the not-too-distant future, it may be possible for anyone to track drusen at home using a special retinal imaging device.

Once you have dry AMD, you need to be monitored at regular doctor visits and through at-home testing.

The best way to check your own vision is to cover one eye at a time, look at a piece of graph paper, and note whether any lines seem wavy or are missing portions. Even better, a simple tool called the Amsler grid, which looks like a piece of graph paper with a dot at the center, should be used regularly for each eye.

It’s important to test one eye at a time, since you can lose a significant amount of vision in one eye without noticing it, because the healthy eye compensates for the failing one. If you see any change in the way these lines and grids appear, you should notify the doctor immediately. It could mean you’re developing the more advanced wet AMD.

Staying vigilant increases the chance you can halt further damage by starting treatment as soon as possible.

Q: What, if Anything, Can Be Done to Prevent Dry AMD From Becoming the Wet Form of the Disease?

A: The best current preventives are AREDS, age-related eye disease supplements. These antioxidants probably function by inhibiting free radical damage and have been used for 10 years to reduce the risk of progression from intermediate to advanced AMD.

If the disease has become wet, though, it means that abnormal blood vessels have grown into the retina. These fragile vessels, which don’t belong in this part of retina in the first place, easily develop holes that release fluid or red blood cells into the eye. The buildup prevents the neurons in the macula from functioning properly, creating a “visual blind spot.”

We know that a particular protein, VEGF, serves as a kind of fertilizer for these defective blood vessels. That’s why we focus treatment on eliminating that protein through special anti-VEGF injections directly into the eye’s fluid center. Before the anti-VEGF injections were introduced about 16 years ago there was no reliable way to keep AMD from worsening, although we did have some treatments.

Q: What’s the Current Treatment, in Most Cases?

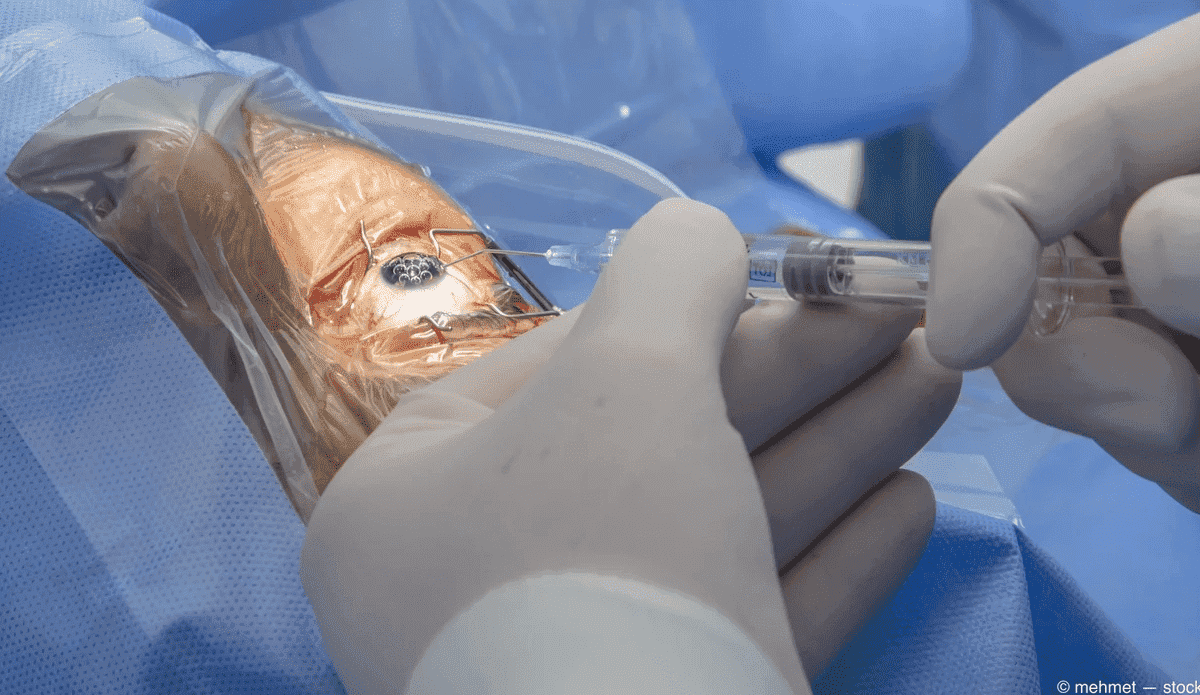

A: For most wet AMD patients, we inject a tiny amount of one of the anti-VEGF drugs into the vitreous fluid within the center of the eye every four to six weeks. This is a procedure done in the doctor’s office.

Since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first of these anti-VEGF drugs, we’ve been remarkably successful in slowing the growth of harmful blood vessels and stopping their leakage. The majority of wet AMD patients who stick with their injection schedule can now maintain pretty good central vision and are able to perform many activities as they did before AMD. In some cases, the drug is so effective that the retina dries up and some of the lost vision is restored.

Before these injections, we used different types of laser treatments that only somewhat slowed vision loss but fell short of totally stopping or improving sight loss. Laser is now used only for the tiny percentage of patients who fail to respond to anti-VEGF injections.

The biggest problem today has less to do with treatment than compliance; getting patients to stick to their regular injection appointments. It’s difficult for an elderly patient who may be juggling multiple medical problems — and may have no dependable transportation to the doctor — to maintain the monthly appointment schedule. Because of that, research is now focused on lengthening the time between the injections.

Some new medications aim to stretch out the period between visits. Just recently, the FDA approved a device that implants a port into the white portion of the eye, where it steadily delivers medication. Patients who have this one-time surgery don’t require monthly or every-six-weeks injections. They do have to visit the doctor at least once every six months to refill the drug reservoir.

As ophthalmologists, we know how hard frequent ocular injections can be for patients. But the alternative is really tough; losing some sight. Regular treatments enable wet AMD patients to not just preserve their existing vision, but to occasionally improve it.

Q: How Significant Is the Fear of Having an Injection Into the Eye? How Do You Deal With It?

A: The idea of an injection into the eye is scary. So, the initial visit always comes with some fear. I try to minimize that by sitting down with the patient before we start and explaining the entire procedure in detail, starting with the initial drops we give to numb the eyes. After the eye is fully numbed, I clean the eye surface and eyelids with an iodine eyewash solution so that they won’t get an infection. I also use an eyelid holder to help the patient keep the eye open and minimize the risk of infection. When the cleaning is done, I ask the patient to look upwards.

Once the patient is fully prepared and I’ve found the perfect injection site, I take a tiny needle that’s thinner than a human hair and insert it into white portion of the eye for the few seconds it takes to introduce a tiny amount of medication into the vitreous fluid in the eye’s center.

Some people may feel a bit of discomfort or some momentary pain or pressure, or they may see some swirly lines as the medication mixes with the fluid in their eye. But it is very brief. The whole process takes a matter of minutes, with most of the time spent preparing the eye for the injection. The shot itself lasts a few seconds.

Afterwards, the eye may be red and irritated for a day or two because of the cleaning, but things typically return to normal within a few days.

If someone is still very concerned, I’ll encourage them to visit a support group so they can hear other people discuss their own experiences with the treatments. Most of the time, the patients come away feeling very reassured. And, of course, I always remind them that the alternative — the prospect of losing some of their central vision — is far worse than the momentary injection.

Q: What Are the Risks if an AMD Patient Also Has Another Eye Condition, Such as Dry Eye, Glaucoma, Cataracts, or Diabetic Retinopathy?

A: All these diseases are independent of AMD.

Patients frequently ask if having dry eye increases the risk for dry macular degeneration. The answer is no. Dry eye results from inadequate tear film on the surface of the eye. It has no effect on the retina, which is located inside the eye.

Some patients also wonder whether cataract surgery will promote AMD. Studies have shown that it doesn’t. A cataract, again, affects an entirely different part of the eye. It’s a clouding of the lens that can prevent light from getting to the retina. Having a cataract and having cataract surgery have no effect on AMD or its treatments.

Glaucoma, which is caused by high eye pressure, is totally separate from AMD, as is diabetic retinopathy.

However, there are some systemic diseases that are associated with AMD. That includes cardiovascular disease (CVD), probably because systemic inflammation is believed to play a role in both these conditions. There’s a marker in the blood in both AMD and CVD that’s called C-reactive protein (CRP), which indicates inflammation in the body. CRP is considered a risk factor for both cardiovascular and macular degeneration. Interestingly, a study that I recently published with my brother, David Dunaief, MD, an internist, showed that eating a plant-rich diet may allow patients to rapidly reduce their levels of C-reactive protein.

Q: What Other Factors Should Wet AMD Patients Be Aware Of?

A: They should know that AMD may predispose them to something called “slow dark adaptation.” That’s what occurs when you walk into a dark room — such as a movie theater — and struggle to see anything. Because AMD affects the sensitivity of the retina, where light is perceived, the AMD eye is not good at adjusting to a sudden change in light. This has nothing to do with the dilation of the pupil. It’s entirely related to the condition of the retina itself. Patients need to prepare for situations with sudden or dramatic changes in light.

They should also understand that sight loss carries the risk of visual hallucinations. We know that people lacking a fair amount of their central vision sometimes develop Charles Bonnet syndrome, a strange symptom in which they may report “seeing” patterns, very much like wallpaper, or “seeing” people or animals that aren’t there. This is caused by a process similar to the phantom limb syndrome, in which an amputee senses real pain in the missing body part.

When vision is partially absent, the brain apparently responds to the lack of stimulation by creating or recalling its own images. It can be terrifying, and people first experiencing it often think that they’re losing their mind. But this is definitely not a psychiatric illness. It’s a fairly common brain response that affects about 25 percent of people who lose some central vision.

Q: What Do We Know About the Role Inflammation and Immunity Play in AMD?

A: There are phase 3 clinical trials that indicate that inhibiting the activation of an immune system product, called complement, may help slow the progression of geographic atrophy (GA), an advanced form of macular degeneration. Complement activation is toxic to retinal cells, and it can also recruit harmful white blood cells to the retina. The use of the anti-complement formulation pegcetacoplan, which would be administered by injection as with anti-VEGF medications, is now under FDA review. It’s possible that by sometime in 2022, the Apellis drug Empaveli may become available for GA.

Q: You Mentioned That Diet and Lifestyle May Be Important in AMD. In What Ways?

A: I suggest a low-inflammatory diet for my patients, such as the LIFE eating plan, which stands for low-inflammatory foods every day. As with smoking, consuming a poor diet with a lot of animal products and processed foods contributes to age-related chronic diseases, including AMD. The same can be said for obesity and a sedentary lifestyle. Conversely, sticking with a plant-rich diet that includes fatty fish twice a week, while maintaining a healthy weight and engaging in regular exercise, is likely to reduce the risk that AMD will develop later. The so-called SAD — Standard American Diet — has reached epidemic proportions that affect many diseases.

Also, while no particular lifestyle or diet is scientifically proven to halt wet AMD, it’s possible — based on associations — to say that exposure to bright sunlight over a long period of time seems to harm the retina. I encourage people to limit their exposure to sunlight and to wear sunglasses whenever they’re in bright light or doing daytime driving. Standard sunglasses are generally fine, particularly if they’re grey or brown-colored. The glasses should be dark enough to filter out harsh light, but not so dark that you can’t see where you’re going. Polarization also helps limit the amount of light that gets to the eye and can also reduce glare.

Q: What’s the Best Way Wet AMD Patients Can Ensure They Get the Best Possible Care?

A: The best way in which they can participate in their own care is by following up with their ophthalmologist to get the injections on time. I’m hopeful that the frequency of injections will be reduced, especially because there are some recent developments that are very promising. There are new medications, interesting clinical trials, and many researchers at eye institutions around the world studying wet AMD.

People with advanced AMD can also help everyone by finding and participating in an appropriate clinical trial, especially if they are progressively losing vision despite current treatments. Their ophthalmologist will know if they qualify for an available trial, or they can check to see which trials are ongoing.

ClinicalTrials.gov maintains searchable lists of trials and their locations. There are often complex qualification criteria, so they have to do some looking around. But they can always work with their doctors to determine which trial makes the most sense.

Of course, in any trial there’s the risk of being assigned to the placebo group, which means you wouldn’t get to test the newest treatment. But with half to two-thirds of trial subjects often receiving the new medication, the odds are pretty good. And everyone gets the standard-of-care treatment at the current time, so there’s no chance your AMD will go untreated. You’ll have the satisfaction of knowing your participation may benefit many others in addition to helping researchers discover which treatment is best for you.

Q: Where Do You Predict AMD Treatment Will Be in 5 or 10 Years?

DD: I’m certain that new treatments for wet AMD will require less frequent doctor visits than the current ones. Instead of a shot every month, patients will receive them every few months, or even only once or twice a year.

Also, gene therapy approaches currently being tested may even provide a “one and done” solution. And new drug targets, in addition to VEGF and complement, will be identified to make treatments more effective.

Stem cell approaches currently being tested may enable the replacement of retinal cells that have died, or they may encourage existing retinal cells to divide and replace missing ones.

Meanwhile, preventive measures, such as specific diets, like the LIFE diet, and antioxidants, will reduce the risk of getting AMD in the first place.